Vietnam becoming next global manufacturing hub

Sayed Abdullah

Vietnam’s economy is the 44th-largest in the world and since the mid-1980s Vietnam has made the tremendous transformation from a highly centralized command economy with support from an open market-based economy.

Not surprisingly, it is also one of the fastest-growing of the world’s economies, with a likely annual GDP growth rate of around 5.1%, which would make its economy the 20th-largest in the world by 2050.

Having said that, the buzzing word in the world is that Vietnam is poised to be one of the biggest manufacturing hubs with the possibility of taking over China with its great economic strides.

Notably, Vietnam is rising as a manufacturing hub in the region, predominantly for sectors like textile garment and footwear and electronics sector.

On the other hand, since the ’80s China has been playing the role of a global manufacturing hub with its huge raw materials, manpower and industrial capacity. Industrial development has been given substantial attention where machine-building and metallurgical industries have received the highest priority.

With relationships between Washington and Beijing in freefall, the future of global supply chains is tentative. Even as unpredictable White House messages continue to raise questions about the direction of U.S. trade policy, trade war tariffs remain in effect.

Meanwhile, the fallout from Beijing’s proposed national security law, which threatens to constrain Hong Kong’s autonomy, further endangers the already fragile phase one trade agreement between the two superpowers. Not to mention rising labor costs mean China will pursue a less labor-intensive high-end industry.

This roughness, paired with the race to secure medical supplies and develop a COVID-19 vaccine, is provoking a re-evaluation of just-in-time supply chains that privilege efficiency above all else.

Simultaneously, the COVID-19 handling by China has given rise to many questions among western powers. Whereas, Vietnam is one of the primary countries to ease social distancing measures and reopen its society as early as April 2020, where most countries are only starting to cope with the severity and spread of COVID-19.

The world is stunned by Vietnam’s success during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Vietnam’s prospect as manufacturing hub

Against this unfolding global scenario, the rising Asian economy – Vietnam – is poising itself to become the next manufacturing powerhouse.

Vietnam has materialized as a strong contender to grasp a big share in the post-COVID-19 world.

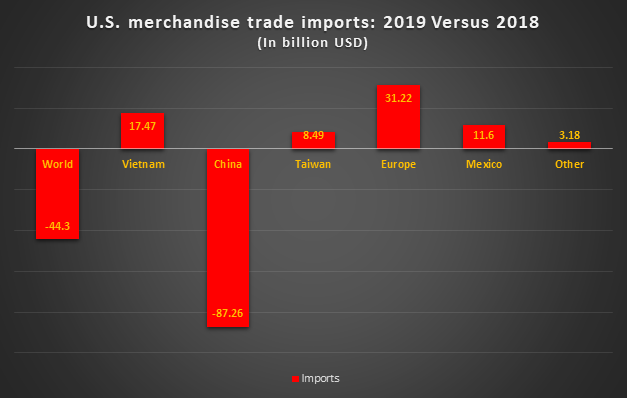

According to the Kearney US Reshoring Index, which compares US manufacturing output to its manufacturing imports from 14 Asian countries, surged to a record high in 2019, thanks to a 17% decline in Chinese imports.

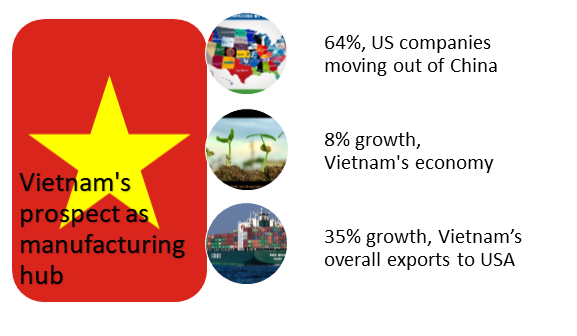

The American Chamber of Commerce in South China also found that 64% of US companies in the south of the country were considering moving production elsewhere, according to a Medium report.

The Vietnamese economy grew by 8% in 2019, aided by a surge in exports. It is also slated to grow by 1.5% this year.

The World Bank prediction in a worst COVID-19 case situation that Vietnam’s GDP will drop to 1.5% this year, which is better than most of its South Asian neighbors.

Besides, with a combination of hard work, country branding, and creating favorable investment conditions, Vietnam has attracted foreign companies/investments, giving manufacturers access in ASEAN free trade area and preferential trade pacts with countries throughout Asia and the European Union, as well as the USA.

Not to mention, in recent times the country has fortified medical equipment production and made related donations to COVID-19 affected countries, as well as to the USA, Russia, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, and the UK.

Another significant new development is the likelihood of more US companies’ production moving away from China away to Vietnam. And Vietnam’s portion of US apparel imports has profited as China’s portion in the market is sliding – the country even exceeded China and ranked the topmost apparel supplier to the US in March and April this year.

The data of the US merchandise trade of 2019 reflects this scenario, Vietnam’s overall exports to the USA rose by 35%, or $17.5 billion.

For the last two decades, the country has been transforming immensely to cater to a wide range of industries. Vietnam has been shifting away from its mostly agricultural economy to develop a more market-based and industrial-focused economy.

Bottleneck’s to overcome

But there are a lot of bottlenecks to be dealt with if the country wants to shoulder with China.

For example, Vietnam’s nature of cheap labor based manufacturing industry poses a potential threat – if the country does not move up in the value chain, other countries in the region such as Bangladesh, Thailand or Cambodia also provide cheaper labor.

Additionally, with the government’s utmost efforts to bring more investments into hi-tech manufacturing and infrastructure to line up more with the global supply chain, only a limited multinational company (MNCs) have limited research and development (R&D) activities in Vietnam.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposed that Vietnam is heavily dependent on imports of raw materials and only playing the role of manufacturing and assembling products for exports. Without a sizable backward linking support industry, it will be a wishful dream to cater to this magnitude of production like China.

Apart from these, other constraints include the size of the labor pool, accessibility of skilled workers, the capacity to handle a sudden outpouring in production demand, and many more.

Another paramount arena is Vietnam’s micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) – comprising 93.7% of the total enterprise – are restricted to very small markets and are not able to expand their operations to a broader audience. Making it a serious choke point in trouble times, just like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, it is vital for businesses to take a backward step and reconsider their repositioning strategy – given that the country still has many miles to catch up with China’s pace, would it be eventually more reasonable to go for the ‘China-plus-one’ strategy instead?